Science should be more than just reading about concepts—it should be something students can see, touch, and explore. When students actively engage with science through hands-on activities, technology, and even literature connections, they develop not only essential science skills, but also deeper understanding and lasting curiosity.

Bringing science to life: Hands-on activities

Perhaps the most effective way to engage students in science is to combine a high-quality curriculum with an interactive teaching style to make it experiential. In my classroom, we use the Amplify CKLA Geology unit to dive into earth science concepts. While these strategies can be applied across grade levels and scientific topics, the following is an example from my fourth-grade classroom’s geology lessons:

- Examining geodes: Students predict what they will find inside before breaking geodes open. Then they analyze the crystal structures, connecting their observations to Amplify CKLA’s science concepts.

- Writing about Earth’s layers: After learning about the Earth’s structure, students reinforce their understanding by writing creative descriptions or short stories from the perspective of different layers.

- Diagramming volcanoes and the rock cycle: Drawing detailed diagrams, students visualize how rocks change over time and how volcanic eruptions shape the Earth’s surface.

Connecting literacy skills to science skills

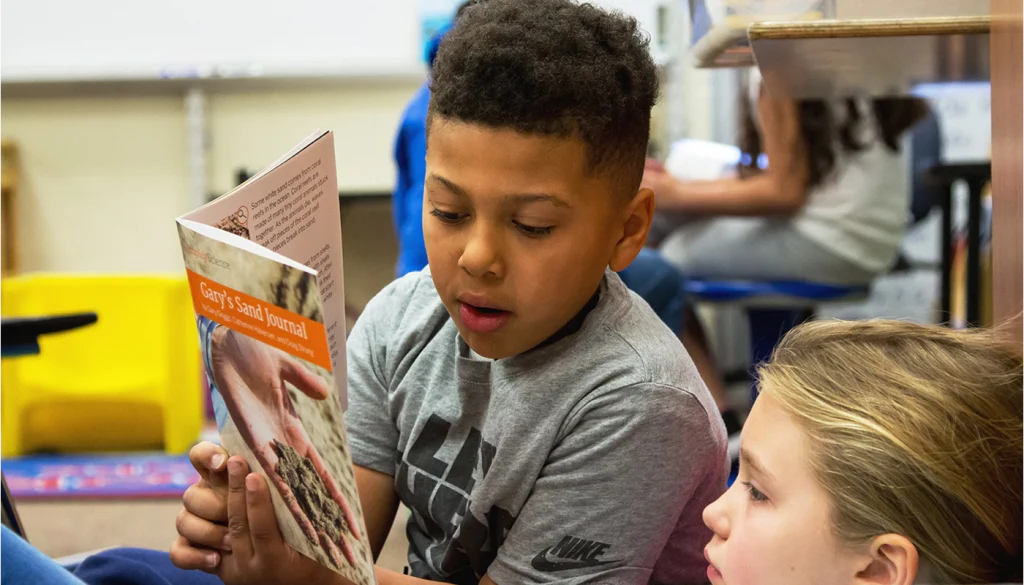

Incorporating literature deepens students’ understanding of science. I use a mix of trade books and digital resources to bring concepts to life through storytelling and informational texts. These books help students connect scientific ideas with real-world applications, fostering both literacy and science skills.

Literacy skills like reading comprehension and critical thinking are key to understanding complex scientific ideas. When students dive into science-related materials, they practice making sense of data, thinking critically about evidence, and building arguments. These practices boost students’ overall literacy, expanding their vocabulary, sparking their curiosity, and developing their media literacy.

Digital resources for students: Exploring science with Google Earth

To further engage students, I integrate Google Earth into our lesson plans. This allows them to explore real-world scientific phenomena—such as geological formations, ecosystems, and weather patterns—making abstract concepts more tangible. Students love zooming in on famous landscapes, discussing how they were formed, and identifying scientific features. This interactive approach using relevant digital tools helps make science feel relevant and exciting.

Final thoughts: The power of engagement in science

By combining hands-on activities, literature, and technology, I’ve helped my students develop a genuine curiosity about science. As the school year progresses, they ask more questions, make deeper connections, and take ownership of their learning.

Engaging students in science doesn’t have to be complicated—it just has to be meaningful. By making learning interactive, Amplify (through Amplify CKLA and Amplify Science) helps students connect with scientific concepts in meaningful ways. I encourage other educators to bring Amplify’s lessons to life with interactive approaches that spark wonder and excitement in young scientists.

Explore more

- Let’s keep the conversation going! Join the discussion in our Amplify learning communities.

- Looking for inspiration? Watch Teacher Connections, a video series featuring practical advice and tools straight from fellow educators—our very own Amplify Ambassadors.

- Dive into our podcast hub to hear from top thought leaders and educators and uncover cross-disciplinary insights to support your instruction.